The Minuscule Monk: A Lizzie Borden Girl, Detective Mystery begins with a quotation from “Antigonish”, a poem by Hughes Mearns (1875–1965).

Last night I saw upon the stair

A little man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

Oh, how I wish he’d go away

I chose this quotation because it perfectly describes the theme that I had woven into the story as a whole. The little man who wasn’t there obviously resonates with the Minuscule Monk himself, and his doubtful existence mirrors the “subjective idealism” coveted by C.B.M. Borden, the boy detective, and his weird delusion that his own mother doesn’t exist.

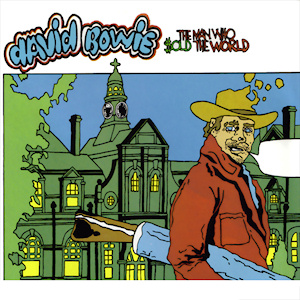

My first introduction to the lines was a David Bowie album that I bought in 1978 at a West Village record store. Bowie had re-conceived the poem with surrealistic lyrics for the song “The Man Who Sold the World.” It was only after Nirvana resurrected it in a 1994 acoustic grunge version that I discovered the lyrics were referencing the Hughes Mearns poem.

My first introduction to the lines was a David Bowie album that I bought in 1978 at a West Village record store. Bowie had re-conceived the poem with surrealistic lyrics for the song “The Man Who Sold the World.” It was only after Nirvana resurrected it in a 1994 acoustic grunge version that I discovered the lyrics were referencing the Hughes Mearns poem.

Mearns was a teacher, notably at the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy and later at Columbia University, and part of the progressive movement in American education started by John Dewey. The poem is a logical absurdity, similar to the mind twisting paradoxes in poems by Lewis Carol or Dr. Seuss. One can imagine a school room full of children laughing uproariously at this “little man who wasn’t there,” a sort of anti-matter doppelganger to the poem’s narrator. It isn’t a far leap from this non-existent imp to other tricksters such as Rumpelstiltskin, Superman’s Mr. Mxyzptlk or the Great Gazoo from the Flintstones. One could also think of Q from Star Trek: The Next Generation or Bugs Bunny, all agents of chaos and logical confusion.

Leave it to avant-rock star David Bowie to refashion this elusive but playful character into a much more haunting and surrealistic one.

On a 1970 album release whose lyric references ranged from Friedrich Nietzsche to H.P. Lovecraft to Kahlil Gibran, Bowie inserted a mysterious track called “The Man Who Sold the World”:

We passed upon the stair, we spoke of was and when

Although I wasn’t there, he said I was his friend

Which came as some surprise, I spoke into his eyes

I thought you died alone, a long long time ago

The overall mystical tone of the album is unmistakable. Here the encounter with the Little Man Who Wasn’t There, a relatively amusing character for children who appreciate fairy creatures, is turned into a breakdown of identity and a descent into madness.

Here it is the narrator who is non-existent (“Although I wasn’t there”). They seem to have a past together and the man may or may not be a ghost (“I thought you died alone”). Bowie’s characteristic bending of lyrics into dark paradoxes is reflected in the phrase, “I spoke into his eyes” which is an act that is hard to visualize but is stylistically perfect for this dreamlike song.

Oh no, not me, I never lost control

You’re face to face, With The Man Who Sold The World

“Not me” is reminiscent of Samuel Beckett’s “Not I”, another exploration of the fracturing of self-consciousness. Perhaps the “world” that the man in the song has “sold” is a total state of being, experienced only by the narrator in the depths of a madhouse. It could also mean a frightening bout of mental illness in which reality becomes elusive and the victim cannot distinguish between himself and other people.

“Not me” is reminiscent of Samuel Beckett’s “Not I”, another exploration of the fracturing of self-consciousness. Perhaps the “world” that the man in the song has “sold” is a total state of being, experienced only by the narrator in the depths of a madhouse. It could also mean a frightening bout of mental illness in which reality becomes elusive and the victim cannot distinguish between himself and other people.

Some people have speculated if there had been a political message in the song, accented by the cartoon cover art in which a cowboy walks by a Federal-style building with a concealed rifle tucked under his arm. I tend to doubt this interpretation since the cover art really depicts the Cane Hill Mental Asylum in England where David Bowie’s brother Terry had been treated for schizophrenia (Charlie Chaplin’s mother Hannah had been treated at Cane Hill as well). If anything, the song could be an homage to his brother who committed suicide in 1985, too late for the song to be referring to Terry’s death. Bowie was wise to keep the meaning of the song mysterious. It is much more effective that way.

SNL recently posted a video of David Bowie performing this song in 1979 accompanied by back up singers Joey Arias and Klaus Nomi. The surreal costume and make-up were to an American audience used to more conventional rock-and-roll attire. It seemed closer to punk, but was too theatrical, too clean. Bowie had just spent several years working in Berlin where he recorded a trilogy of albums with Brian Eno and had a lot of exposure to the European art and music scene. His act with clownish costumes and mime-like gestures would have fit in beautifully at a Dada festival. In regard to the song, the theatrical effects heightened its sense of otherworldliness.

The song was revived again in 1993 when Nirvana, just months before their lead singers’ suicide, performed an acoustic version on MTV’s unplugged series. In stark contrast to the SNL theatricality, the song is performed by an unshaven grunge artist with uncombed hair and shabby clothing. Cobain’s vocals are gruff with less acting but no less haunting. He makes no eye contact with the audience and at times mumbles the lyrics, but he seems inwardly focused.

Considering that “The Man Who Sold the World” had been an obscure Bowie track from a pre-Ziggy album, the Nirvana performance was many Generation X-ers introduction to the song. The contrast between German 80s art-rock and Seattle 90s grunge can’t be greater, but the song thrived in both treatments because of its timeless and unsettling elements.

While The Minuscule Monk is a few cry from a David Bowie or a Nirvana album, it does depict several characters having crises of consciousness. They all respond in their own characteristic way. Andrew Borden grows increasingly frustrated and becomes mentally confused. C.B.M. Borden, having been raised by a woman of dubious mental stability, is already skeptical of reality and tries to cover it up with philosophical rationalization and a forced self-confidence. Herr Hugo von Trotter, the Truth-Telling Dog, fights back with a violent campaign against human lies, refusing to let them get away with it.

It is only Lizzie who plows forward with a determination to reconstruct reality and expose the truth. But her evidence keeps disappearing, people turn out to be other than what they claimed, and those about her are weaving alternate realities that is counter-productive to her investigation.

For these reasons, the Mearns poem seemed appropriate. It struck a tone, announced a theme. And I have to admit, I had more than a few musical hooks from David Bowie’s song in my mind as I wrote.